In Part 1 of this feature essay, Sundari Anitha and Ruth Pearson introduce their new book, Striking Women: Struggles and Strategies of South Asian Women Workers from Grunwick to Gate Gourmet, which focuses on two industrial disputes in the UK: the famous Grunwick strike (1976-78) and the Gate Gourmet dispute of 2005. The book gives a voice to the women involved in the strikes and explores South Asian women’s contribution to the struggles for worker’s rights in Britain.

If you are interested in this book, you may also want to visit the interactive website www.striking-women.org, created by the authors for schools and community groups and offering resources on migration, women’s and labour rights based on research on South Asian women in the UK.

Striking Women: Struggles and Strategies of South Asian Women Workers from Grunwick to Gate Gourmet. Sundari Anitha and Ruth Pearson. Lawrence and Wishart. 2018.

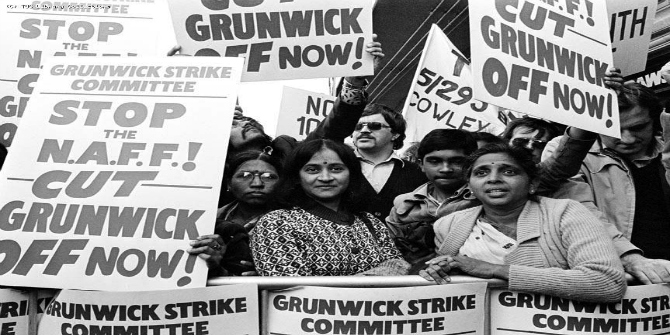

2018 marks the fortieth anniversary of the end of the emblematic Grunwick strike, an event which is writ large in the annals of British trade union history. Grunwick is still remembered as the moment when the trade union movement took the cause of migrant and women workers to its heart. This was seen as the point at which intersectionality was embraced by organised labour in the UK, which led to the espousal of anti-racist policies and an end to support for the privileges of the male labour aristocracy – either as breadwinners or as full-time established workers.

2018 marks the fortieth anniversary of the end of the emblematic Grunwick strike, an event which is writ large in the annals of British trade union history. Grunwick is still remembered as the moment when the trade union movement took the cause of migrant and women workers to its heart. This was seen as the point at which intersectionality was embraced by organised labour in the UK, which led to the espousal of anti-racist policies and an end to support for the privileges of the male labour aristocracy – either as breadwinners or as full-time established workers.

However, the story is more complicated. Firstly, the Grunwick strike ended in defeat. The much-heralded and broad support for the mainly South Asian women strikers, most of whom were twice migrants from countries in East Africa, where they had settled during British colonial rule, evaporated in the face of a conservative union leadership and Trades Union Congress (TUC) yielding to fears about social unrest and political disaster in the dying days of the Labour government in 1977. As Jayaben Desai, the iconic strike leader, famously quipped:

Trade union support is like honey on the elbow – you can smell it, you can feel it, but you cannot taste it.

By March 1978 the mass pickets of the previous year had disappeared; the boycotting of the post by the Postal Workers’ Union, an effective tool to pressurise a mail order business, had been overruled; and the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (Acas)-appointed Scarman Inquiry, which found in favour of the strikers’ main demands for union recognition, collective bargaining and reinstatement, had been ignored by the litigious Anglo-Indian owner of Grunwick, George Ward. But the centrality of Grunwick to contemporary trade union narratives lives on.

Our new book, Striking Women: Struggles and Strategies of South Asian Women Workers from Grunwick to Gate Gourmet, interrogates this narrative. It focuses on the political and personal agency of the women strikers themselves, unlike previous accounts including Jack Dromey and Graham Taylor’s well-known Grunwick: The Workers’ Story (originally published in 1978 and republished in 2016 to mark the fortieth anniversary of the start of the strike), which predominantly concerns the itinerary of the industrial dispute, and Joe Rogaly’s Grunwick (1977). These earlier books rehearse the familiar story of how workers at the film processing plant in North West London were so exasperated and offended by the overbearing and arbitrary management that they walked out; how a small group of South Asian workers grew to a significant number under the leadership of the indomitable Desai, guided and supported by the Brent Trades Council, including the then-youthful Dromey. They recount how support for the strikers spread to other well-organised unions, including the National Union of Mineworkers and the previously protectionist and anti-immigrant London dockers, and how the strategy of mass picketing was supported not only by trade unionists up and down the country, but also by large sections of the left as well as the women’s movement and anti-racism activists.

Image Credit: Grunwick strikers picketing 1977 © TUC Library Collections, part of Special Collections at London Metropolitan University

The authorised story of the dispute, favoured by trade unions, does not dwell unduly on the ultimate defeat, or even the lack of sustained or robust commitment on the part of particular unions in the face of a changing political and economic landscape which saw the Labour government fall victim to heightened anti-union scapegoating. Instead it focuses on its trajectory, the escalation of the picketing, the details of the Scarman Inquiry and the tactics used by the Grunwick owner and his right-wing allies to outwit the actions of the wider labour movement to increase the pressure on the firm. But it says little about who the strikers were, how they experienced the long years of this dispute or what their lives were like before and after.

Striking Women, on the other hand, is rooted in the lived experience of the women strikers. Although the surviving Grunwick strikers were quite elderly when we undertook our initial research in 2007-10, we were able to interview four other South Asian women ex-strikers in addition to carrying out an extensive interview with Desai, who died in 2010. Because we were able to talk to the women in Hindi and sought the women’s work/life histories rather than just their memories of the strike and its aftermath, we captured a more nuanced understanding of their lives. We were able to access a broader account of how they were able to juggle their responsibilities at home with the requirements of their job, which reinforced the finding that one of the most unacceptable aspects of the harsh management regime at Grunwick was the imposition of arbitrary overtime which made it too difficult to manage these competing demands.

We also gained a deeper understanding of the intersecting dynamics of the situation these migrant workers were faced with as low-paid workers in an increasingly hostile country, working in a new, unregulated and unorganised industry. They had no previous experience of outside paid work or industrial militancy to fall back on, and having occupied an intermediate position in colonial East Africa, they were unprepared for the everyday or institutionalised racism of 1970s London in a country where they had expected to receive a citizen’s welcome. The managerial controls played on these gendered and racialised hierarchies to exercise maximum productivity from the workers. It is not surprising that in the years following the dispute, the actions of the striking women continued to be celebrated through what can be seen as an orientalist lens, as the media and others repeatedly expressed their surprise at these short and feisty ‘strikers in saris’: a view that reinscribes stereotypes of the passive South Asian woman.

This is Part 1 of the two-part feature essay introducing the book. The second part will be published next week. This article was first published on LSE Review of Books and is republished here with permission, the original can be accessed here.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About The Authors

Sundari Anitha is Reader at the School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Lincoln. She has researched and written on two areas of labour market experiences of South Asian women in the UK, and on violence against women and girls in the UK and India. Her publications include Gender Based Violence in University Communities (Policy Press, forthcoming 2018); Disposable Women (University of Lincoln, 2016); and Forced Marriage(Zed Books, 2011). She has been also active in campaigns and policy-making to address violence against women since 1999 and is a trustee of several UK-based charities.

Ruth Pearson is Emeritus Professor at the University of Leeds and a feminist economist who has researched and written about women’s work in the global economy since the 1970s, focusing in recent years on migrant workers and gendered globalisation. She is the co-author, with Diane Elson, of the classical article on women workers in export production: ‘Nimble Fingers make Cheap Workers’ (Feminist Review, 1981). More recent books include Thailand’s Hidden Workforce (Zed Books, 2012) and Globalization, Export-Orientated Employment and Social Policy (Routledge 1998). She has also been an activist in a range of women’s organisations and has acted as a consultant and/or academic advisor for a number of international organisations including UNDP, Oxfam, Action Aid and DFID.